Learning to live with our enemies

By Christopher Ryan Maboloc, PhD

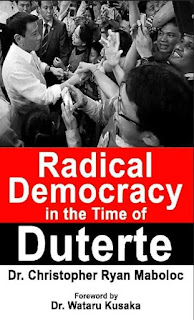

In his Foreword to my forthcoming book, Radical Democracy in the Time of Duterte, Wataru Kusaka mentions my provocative approach to writing. I invited him to write the Foreword knowing that he is an objective reader and told him that I will take his thoughts on my work positively. Such constructive criticism is important since I actually got interested in difference politics after reading his Moral Politics in the Philippines.

Many times, my critics have attacked my ideas, and sometimes my person on social media. I welcome such type of antagonism, knowing that our difference in opinion only proves the contested nature of politics in the country. Kusaka explains that my radical democracy thesis offers a way of presenting the underrepresented voices or narrative in Philippine history and politics, although he also disagrees with me on key issues.

Benjiemen Labastin's article, "Two Faces of Dutertismo, Two Visions of Democracy in the Philippines," is an eloquent introduction to my work on President Duterte's radicalism. Labastin is the first to give it justice and he understands the distinction I make between the substantive and the procedural, which can also be seen as the difference between politics and the political.

Kusaka is right to argue that Duterte disrupts the EDSA narrative. My critics may have a point that the fight against the oligarchy has been overshadowed by the rise of new elites. This position is nothing new to me as I have wrote about it in an Inquirer op-ed. Dr. Mansoor Limba, an Islamic scholar from Mindanao, is quick to point out though that my position is a form of decentering that defies metaphysical ruminations.

But the biggest reactions come from my argument that Bongbong Marcos won because EDSA failed. By this, what I wanted to say is that the People Power Revolution failed to fulfill its promises to the Filipino and that the liberals paved the way for the return of the Old Order, as pointed out by Hotchcroft and Rocamora (2003). Of course, many would disagree, but that again only proves the reality of contestation in politics.

Many who voice a different opinion from the grand narrative that is EDSA People Power are being demonized online, suggesting such terms as enablers or fascists and purveyors of disinformation. But that is nothing to be worried about since most detractors have not actually read the complete scope of my writings, let alone published anything on the subject matter. Fair judgment requires suspending one's biases, suggests Dr. Jeffry Ocay.

The saga that is Philippine democracy will continue, Dr. Limba says. Kusaka points out that what is wanting in my work is the fact that people have to go beyond the "us" versus "them" dichotomy. We cannot just destroy a dominant system and replace it with another. Pluralism demands that we must learn to live with our enemies and that will require some kind of respect for another person's perspective.

Power, Michel Foucault writes, does not stay in one place. In this regard, the struggle comes from the desire to maintain one's position. Those who insist on the superiority of their moral position are simply unable to look into their own inner selves and forget that the purpose of radical democracy is never about finding a consensus or a final agreement. It is enough that we recognize the struggle that defines the political.

In the wise words of Fr. Conrado Estafia during a chance encounter in Bohol, he argues that politics is never about morality, but the pursuit of human interests. Fr. Estafia is right. What we need is some form of a re-examination of prevailing systems and structures. But for now, there is no point in debating who is right and who is wrong. People will insist that they are right anyway.